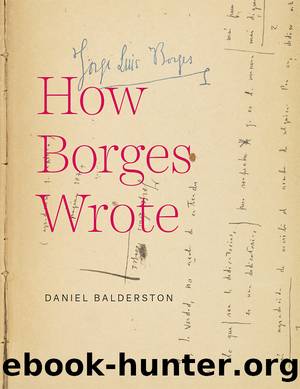

How Borges Wrote by Daniel Balderston;

Author:Daniel Balderston;

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Lightning Source Inc. (Tier 3)

There are much longer sentences in the history of literature2âthink of Joyce, GarcÃa Márquez, Faulkner, Saramagoâbut this one has a wonderful complexity. It is remarkable for its compactness: in 430 words it goes off madly in all directions, at the same time working from a still center: âvi,â I saw. As the narrator (who is called âBorgesâ in the story) says a bit earlier, his problem is how to transmit the infinite Aleph in a finite number of symbols, through the âenumeración, siquiera parcial, de un conjunto infinitoâ (625; the enumeration, even impartial enumeration, of infinity [Collected Fictions 282]).3 His solution, a sentence that Fernando Vallejo has called âel punto culminante de uno de los relatos de Borges (¿o de su obra, acaso?)â (Logoi 203; the highpoint of one of Borgesâs stories [and maybe of his whole work]), is what I will analyze here.

Perhaps the first thing to say about this sentence is that it is wonderfully strange. Unlike his host, Carlos Argentino Daneri, who has used this luminous object to survey the surface of the earth and write plodding quatrains about particular places seen, and who proposes to continueâin a remarkably tedious wayâblock by block, square kilometer by square kilometer, our narratorâs approach to geography is radically unsettling: he records big things, tiny things, some things that are shockingly private (his beloved Beatrizâs obscene letters to her first cousin, his host upstairs), others that are public. The âsystemâ of enumeration here looks like an embrace of chaos, but it gets at a different, and perhaps better, way of expressing the totality than other, more methodical, approaches. Leo Spitzer used the term âchaotic enumerationsâ (in an essay published in Buenos Aires in 1945, the year of publication of the story) for lists that give a bewildering sense of a whole; Sylvia Molloy prefers the term âheterocliteâ to âchaoticâ (193â205), and for good reason: the radical otherness of this list constitutes a kind of order.

In terms of rhetorical structure, it is hard to say anything in general about this sentence since the different clauses of it have a great variety of syntactic structures and of rhetorical strategies, but one thing jumps right out: the sentence is organized around thirty-seven repetitions, at the heads of sequences, of the verb âvi,â I saw.4 (There is also a âviâ in the middle of a clause and, near the end, an âhabÃa visto,â which looks back on the whole sequence.)5 This is a radical use of anaphora, the structure of repetition that is so important in the Bible (and in some modern poetry, including that of Walt Whitman, Vicente Huidobro, and Pablo Neruda, and for that matter in some of Borgesâs later poems). But what comes after the repeated first-person-singular verb implies a lot more than thirty-seven visions: there are many more things, to recall Hamletâs words to Horatio, than are accounted for at first.

As often happens with Borges, the references are mundane and erudite and precise and muddled, encompassing vastly different fields of knowledge, things both natural and artificial, simple and paradoxical.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell & Bill Moyers(925)

Half Moon Bay by Jonathan Kellerman & Jesse Kellerman(908)

A Social History of the Media by Peter Burke & Peter Burke(879)

Inseparable by Emma Donoghue(844)

The Nets of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, James Joyce, and Sigmund Freud by Maud Ellmann(738)

The Spike by Mark Humphries;(719)

The Complete Correspondence 1928-1940 by Theodor W. Adorno & Walter Benjamin(703)

A Theory of Narrative Drawing by Simon Grennan(703)

Ideology by Eagleton Terry;(655)

Bodies from the Library 3 by Tony Medawar(647)

World Philology by(645)

Culture by Terry Eagleton(643)

Farnsworth's Classical English Rhetoric by Ward Farnsworth(641)

A Reader’s Companion to J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye by Peter Beidler(613)

Adam Smith by Jonathan Conlin(605)

Game of Thrones and Philosophy by William Irwin(592)

High Albania by M. Edith Durham(589)

Comic Genius: Portraits of Funny People by(581)

Monkey King by Wu Cheng'en(575)